Shrewsbury Cakes (17th century)

I have occasionally made a delicious Elizabethan style biscuit, known as Shrewsbury Cakes, and the most recent reason for this recipe is an interview by Paul Shuttleworth of BBC Radio Shropshire.

In Elizabethan times, ‘Banqueting’ was somewhat removed from the modern concept of a ‘Banquet’. Delete the stacking chairs, balloons and round tables, and insert sugar, opulence, sugar and more sugar.

As part of these banquets ‘fine cakes’ were served alongside hippocras, sweetmeats and other sweet delicacies. One of these ‘fine cake’ recipes is now known as Shrewsbury or Shropshire Cake, and they were already associated with the town of Shrewsbury by 1596. In that year there was a shortage of grain, and so a ban on the making of ‘fine cakes’ was imposed in Shrewsbury.

In 1602, Lord Herbert of Cherbury wrote to his guardian, Sir George More with a pack of ‘bread’ or ‘cake’ particular to Shrewsbury:

“Lest you think this country ruder than it is, I have sent you some bread, which I am sure will be dainty, howsoever it be not pleasinge; it is a kind of cake which our country people use and made in no place in England but in Shrewsbury; if you vouchsafe to taste them, you will enworthy the country and sender. Measure not my love in substance of it, which is brittle, but the form of it, which is circular”.

The description of those cakes being both ‘brittle’ and ‘circular’, suggests that they are similar to the round shortbreads of later recipes.

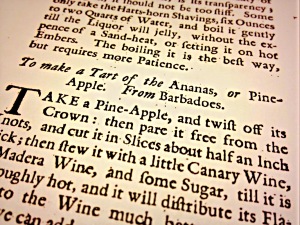

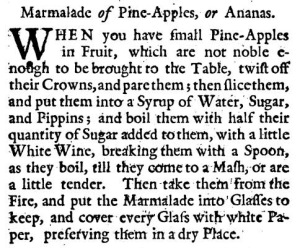

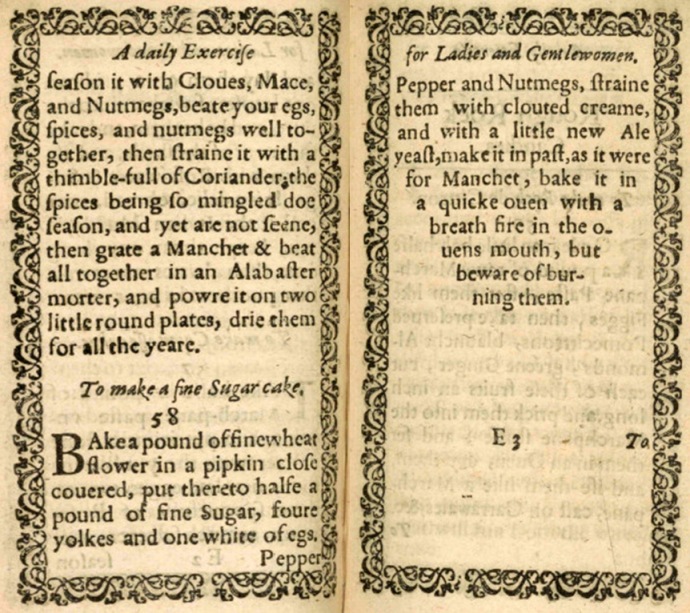

Possibly the earliest recorded recipe for Fine Cakes dates to 1617, from John Murrell’s A Daily exercise for Ladies and Gentlewomen, and is a little more cake-like with the use of yeast.

John Murrell’s recipe for Fine Sugar Cake, from the 1617 ‘A Daily exercise for Ladies and Gentlewomen’.

The full and proper title for this book is:

‘A daily exercise for ladies and gentlewomen : whereby they may learne and practise the whole art of making pastes, preserues, marmalades, conserues, tartstuffes, gellies, breads, sucket-candies, cordiall waters, conceits in sugar-workes of seuerall kindes : as also to dry lemonds, orenges, or other fruits : newly set forth according to the now approued receipts vsed both by honourable and worshipfull personages / by Iohn Murrel, professor thereof’!

Peter Brears records an excellent and useful recipe from the mid 17th century for Madame Susan Avery’s Shropshire Cakes in his ‘Traditional Food in Shropshire‘:

TO MAKE A SHROPSHIRE CAKETake two pound of dryed flour after it has been searced fine, one pound of good sugar dried and searced, also a little beaten sinamon, or some nottmegg greeted and steeped in rose water; so streene two eggs, white and all, not beaten to it, as much melted butter as will work it to a paste; so mold it and roule it into longe roules, and cutt off as much at a time as will make a cake, two ounces is enough for one cake: then roule it in a ball between your hands: so flat it on a little white paper cut for a cake, and with your hand beat it as big as a cheese trencher and a little thicker than a paste board: then prick them with a comb not too deep in squares like diamon and prick every cake in every diamon to the bottom; so bake them in an oven not too hot: when they rise up white let them soake a little, then draw. If the sugar be dry enough you need not dry but searce it; you must brake in your eggs after you have wroat in some of your butter into your flower: prick and mark them when they are cold: this quantity will make a dozen and two or three, which is enough for my own at a time, take off the papers when they are cold.

This recipe is particularly useful as it clearly describes the quantities of ingredients, method of making and what the resulting cake should look like. This is the sort of information that we expect of a modern recipe, but is usually missing in historic recipes. The cheese trenchers described are about 5 inches in diameter, so we have a good idea of the finished product.

My making of Peter Brears’ recipe is as follows:

- 1 lb (450g) Plain flour

- 8 oz (225 g) Butter

- 8 oz (225 g) Caster sugar

- ½ tsp (2.5 ml) Cinnamon

- 1 medium Egg

- 1 tsp (5 ml) Rosewater

- Mix all the dry ingredients together in a bowl, and rub in the butter.

- Work in the egg and rosewater with a round bladed knife.

- Knead lightly to form a stiff dough.

- Divide the dough into 16 equal balls, and pat out into 5” (13cm) rounds.

- Decorate with a comb to form diamond shapes.

- Bake at 180°C (350 °F) for 10-15 minutes.

The purpose behind the patterning is probably functional. The diamond pattern produced with a (clean!) comb allows the large cakes to be broken up into more lady-like pieces to be eaten. You can not imagine an aristocratic Jacobite lady trying to wedge a 5 inch wide cake into her mouth! The prick mark in the middle of each diamond allows the heat to evenly enter the whole cake at once allowing even and quick cooking.

These are high status foods, and so are as white as possible. They use highly processed white flour, and expensive white sugar. When cooking, the cakes want to be cooked, but removed before any browning appears on the edges.

These ‘cakes’ or biscuits are delicious and are delicately flavoured with rosewater. I would caution anyone using rosewater as it seems that most supermarkets have changed the main supplier of rosewater to one that is much stronger. I now water my rosewater down to roughly half or a third of the original strength. Rosewater is delicious when subtle, but quite unpleasant when it assaults your taste-buds when too strong!